Why Scientists Are Afraid of the Deepest Caves

Exploring why scientists approach the world’s deepest caves with caution reveals surprising dangers hidden in darkness—biological, geological, and psychological.

Introduction: The Fear Beneath the Earth

In the shadowed depths of the planet, where sunlight has never reached, lies a world as alien as the ocean floor. The deepest caves—some plunging more than two kilometers underground—aren’t merely geological wonders; they are portals into an underworld filled with mystery, danger, and scientific unease. For many cave researchers and speleologists, these dark realms evoke both fascination and fear.

The Hidden Frontier Below

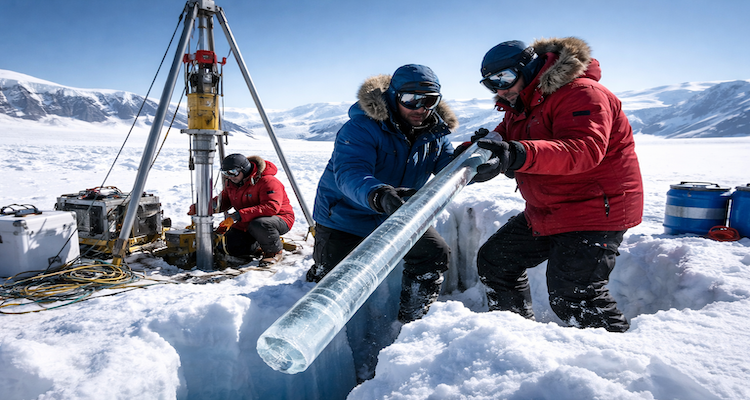

Human curiosity has driven exploration into space and the deep sea, yet the subterranean world remains one of Earth’s most elusive frontiers. Caves like Georgia’s Veryovkina Cave, currently the deepest known at 2,212 meters, or the Krubera Cave before it, are so deep that descending into them feels like entering another planet.

Within these caves, scientists study untouched ecosystems, minerals formed over millions of years, and microbial life that could hint at potential extraterrestrial survival on Mars or Europa. However, as scientific teams venture further, the deeper fear is not simply getting lost—but confronting conditions that challenge the limits of human endurance.

The Dangers Beneath: Why Scientists Hesitate

Deep cave exploration introduces hazards at every step. Temperatures plunge close to freezing. Oxygen levels fall unpredictably. Floodwaters can trap teams for days. Above all, the isolation intensifies every risk. Equipment failure or injury underground can be fatal when rescue operations take days or even weeks.

Geologist Alina Novák of the European Cave Science Institute explains, “Once you pass beyond the 1,000-meter mark, everything changes—pressure, gas concentration, microbial activity. You’re entering an environment that’s biologically and geologically unstable.”

Toxic gases such as carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulfide can accumulate in low-ventilation chambers, rendering sensors unreliable. Even a small misjudgment in air composition can cause dizziness, unconsciousness, or death.

Unseen Life—and Unknown Risks

The fear extends beyond physical danger. Scientists studying deep cave biology are increasingly cautious about what they might uncover. Microorganisms thriving without sunlight feed on minerals or methane, mirroring life conditions that could exist on other planets. However, these microbes can also pose unforeseen biological risks.

In 2024, a research team suspended exploration in a Turkish cave after discovering bacteria previously unknown to science that contained antibiotic-resistant genes. The discovery triggered debate about containment protocols in extreme habitats.

“There’s a duality in these discoveries,” said Dr. Benjamin Cruz, a microbiologist at the International Society for Speleological Research. “They tell us how life adapts to extremes but also remind us that ancient microbial ecosystems might harbor pathogens that have evolved separately for millions of years.”

The Psychological Abyss

Even with advanced gear, the human mind becomes a fragile instrument underground. Hours without natural light unsettle circadian rhythms. The sound of dripping water, echoing infinitely, amplifies anxiety. Claustrophobia is common, and researchers often report a haunting sense of “being watched,” a psychological response to total sensory deprivation.

Military psychologists studying subterranean environments liken the mental strain to space missions—long isolation, confined space, and survival dependency on technology. A 2023 study from the University of Lausanne found that 40 percent of deep cave researchers experienced elevated stress hormones after multi-day expeditions.

A Mirror of the Unknown

Why, then, do scientists keep going back? For many, the caves’ darkness symbolizes humankind’s yearning to know itself. Beneath the layers of rock and danger lie clues about Earth’s history—ancient climate data locked in limestone, or evidence of early human civilizations that once sheltered within.

Exploration also helps predict geological hazards. Cave systems often interlink with aquifers and fault lines, offering insight into how climate change might alter underground water reserves or trigger sinkholes.

Yet, as the world’s deepest sites remain largely unexplored, ethical questions arise. Are scientists risking too much to uncover what lies below? Should exploration be regulated like space missions to ensure safety and environmental preservation?

Impact and the Future of Deep Cave Science

New technologies are changing the field. Robotic probes and autonomous drones equipped with lidar and thermal imaging now explore narrow passages too dangerous for humans. Hybrid suits with climate control may soon allow deeper, longer expeditions. Still, technology cannot fully erase the risk.

The global scientific community is slowly establishing protocols—a kind of “underground ethics code.” These include microbial containment standards, mental health support for prolonged isolation, and environmental safeguards to protect delicate cave ecosystems.

Future studies might help humanity adapt to extraterrestrial habitats using lessons learned deep beneath Earth’s crust. But for now, fear remains an essential companion—one that ensures respect for a world where life and death often hang by a carabiner.

Conclusion: Beyond Fear, Toward Understanding

The fear that scientists feel in the world’s deepest caves is not weakness—it is respect. These caves remind us that even in an age of lunar landings and AI simulations, Earth still holds domains that defy control. For explorers, the journey downward is both scientific and spiritual—a test of courage and humility before nature’s most ancient darkness.

The deepest caves continue to whisper of worlds unseen. Science will keep listening, carefully, one echo at a time.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational and educational purposes only. All statements and quotes are based on referenced scientific understanding as of October 2025.